A new study shows how extraordinary states of consciousness may fundamentally alter how we experience the sleeping mind.

Recent research has uncovered a compelling relationship between near-death experiences (NDEs) and our dream lives, suggesting that these extraordinary states of consciousness may fundamentally change how we experience the sleeping mind — and in ways that are welcome rather than disturbing.

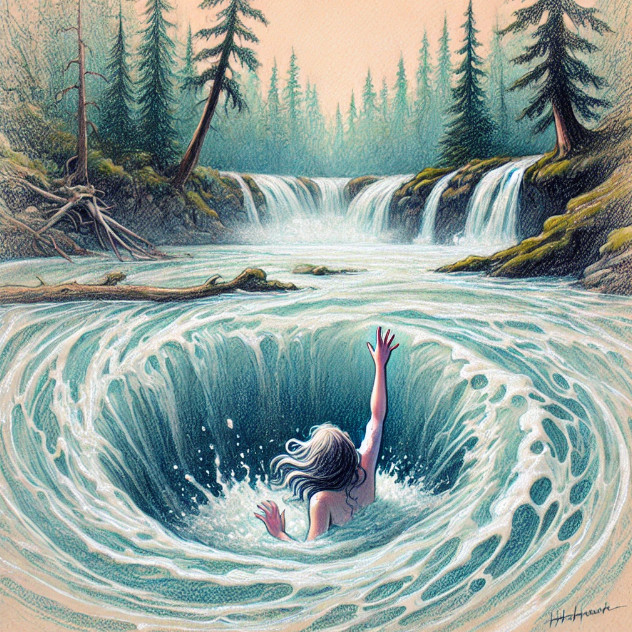

When a new study on near-death experiences (NDEs) and dreaming crossed my desk, it immediately piqued my interest. One of the most profound experiences of my life was a near-drowning when I was 17 that left me in awe. Once my desperation for oxygen subsided, I was transported into a state of calm and was greeted with an all-loving feminine presence that completely assuaged my fears. Although I am very grateful I did not die that day, in the moment, I had reached a surprising degree of acceptance.

I have written about this experience in my book, A Clinician’s Guide to Dream Therapy because years later, I had a dream about this near-drowning that became the basis of a profoundly healing therapy session. My point in bringing up this example in the book was that although we often have dreams that feel highly significant, if we don’t spend time exploring them in a supportive or therapeutic setting, we may lose much of the benefit the dream is bringing.

The recent study in Dreaming had a different aim: to simply examine the relationship between NDEs and various dream phenomena. The researchers compared three groups: 138 individuals who had experienced NDEs, 45 people who had faced life-threatening events without NDEs, and a control group of 129 participants with no near-death events. The results were compelling. NDE survivors reported significantly more lucid dreams (dreams where you know you’re dreaming), creative and problem-solving dreams, precognitive dreams (dreams that seem to predict future events), and out-of-body experiences during sleep.

The researchers found that these experiences appear to be primarily related to the NDE itself rather than the trauma of nearly dying. While trauma symptoms were higher in the NDE group, statistical analysis revealed that the NDE phenomenology—not trauma—was the significant predictor of these enhanced dream states.

My own experience reflects these findings. After my near-drowning, my dream life began to take on a different quality—more vivid, more meaningful, and occasionally lucid. The dream that eventually led me to deep therapeutic insight was not a nightmare that simply replicated my traumatic experience. Instead, it contained symbolic elements that helped me process and integrate the transcendent aspects of my near-death experience. Both the NDE and subsequent dreams about it left me with an accepting attitude towards death that has stayed with me all these years, an experiential sense that something loving exists beyond our usual consciousness.

For me, the study’s findings, which suggest something profound may be happening in the brains of those who have experienced NDEs, comes as no surprise. Rather than simply suffering from trauma-related sleep disturbances, NDE survivors seem to develop an expanded awareness that bridges their waking and sleeping lives.

The researchers note that these atypical dream states share important similarities with NDEs: “These states share clear similarities with NDEs—that is, they typically consist of clear, vivid, and coherent narrative structures devoid of the bizarre, fragmented imagery often characterizing ordinary dreams. Instead, these types of experiences appear to involve higher-order cognitive functions that include heightened self-awareness and self-regulation not normally available during ordinary dreaming.”

While trauma often disrupts sleep, leading to nightmares and fragmented sleep patterns, what’s happening with NDE survivors appears to be qualitatively different. Their dream experiences aren’t characterized primarily by distress but by expanded awareness and sometimes positive transformation. And for clinicians working with such dreams, facilitating further exploration can enhance the likelihood that such dreams facilitate positive shifts.

The study parallels other research on transcendent states. Experienced meditators, for instance, show similar patterns of increased lucid dreaming and neurophysiological changes that persist beyond their meditation practice. The researchers suggest that NDEs—though often brief in objective time—may similarly transform brain functioning in lasting ways. These findings add to a growing body of research suggesting that consciousness is more complex and malleable than we’ve traditionally understood. The relationship between NDEs and expanded dreaming states offers a unique window into how profound experiences can reshape our awareness across different states of consciousness.

My clinical work with dreams has convinced me that dreamwork can be especially valuable for those who have experienced NDEs or other profound spiritual experiences. Dreams provide a bridge between ordinary and non-ordinary states of consciousness, giving us a language to process experiences that often defy conventional understanding. The study findings also highlight the importance of approaching NDEs with nuance. While the trauma of coming close to death certainly impacts many survivors, focusing on the traumatic aspects misses the potentially transformative nature of these experiences. For many, including myself, NDEs represent not just trauma to be overcome but profound experiences that expand our understanding of consciousness and reality.

As the researchers conclude: “Our findings continue to suggest a relationship between non-ordinary states and expanded awareness more broadly—whether experienced during sleep, wakefulness, or somewhere in between.” This research validates what many NDE survivors have reported—that their experiences fundamentally altered their relationship to consciousness, both waking and dreaming. My own near-drowning and subsequent dreamwork supports this connection. My dream didn’t simply replay trauma; it offered a pathway to deeper integration and understanding of an experience that had shaped my perception of consciousness, life, and what might lie beyond.

Lindsay, N., Tassell-Matamua, N., O’Sullivan, L., & Gibson, R. (2025). Trauma or transcendence? The relationship between near-death experiences and dreaming.Dreaming, 35(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/drm0000278