Our dreams, especially our nightmares, are not isolated from our waking lives. Rather, they often mirror our deepest emotional patterns and interpersonal wounds. Emerging research on relational nightmares, defined as disturbing dreams involving interpersonal conflict, loss, or rejection, has found a consistent link to insecure attachment styles, particularly the fearful and anxious types. This makes intuitive sense. As social creatures, we are profoundly affected by our relationships, and when those relationships are fraught, our sleep and dreams can become haunted by unresolved distress.

This dynamic is apparent in my work with dreams. Clara’s story is a vivid illustration. Years after leaving a damaging relationship with John, a charismatic but emotionally volatile partner, she continued to have distressing dreams about him. These dreams didn’t feature overt terror, but were saturated with emotional darkness, feelings of powerlessness, humiliation, and longing. Clara kept wondering, “I’m so over him. Why do I keep having these awful dreams about him?”

The research provides a compelling answer: insecure attachment, particularly the fearful and anxious types (Belfiore & Pietrowsky, 2017; Reed & Rufino, 2019), tends to linger in the psyche and the body, infiltrating both dreams and waking life, even when we think we’ve moved on. People with fearful attachment both crave closeness and fear rejection, a push-pull dynamic that can be emotionally exhausting (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016).

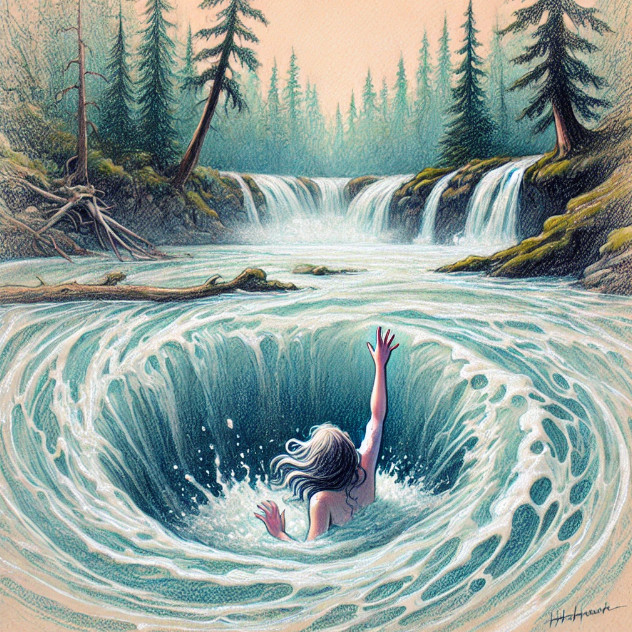

In dreams, these unresolved tensions often take symbolic form. Clara’s dreams were not about John, per se, but about the unhealed attachment patterns he activated. They featured recurring themes of being in danger or distress. In her nightmares, Clara would often find herself in trouble in the wilderness, trapped on a high ledge, for example, or injured and unable to get herself to safety. John would enter the scene, and she would feel hopeful, relieved, expectant of his help. But he would see her in distress and continue on his way without offering any help at all. This always came as a hurtful shock in the dream and she’d wake with a fresh sense of the painful memories of the increasing distance and cruelty she experienced in relationship with him.

In my work with challenging dreams, I also see themes of family conflict that vary dramatically. Some dreams, on the surface, may not seem overly serious—things like not being invited to a baby shower, or being at a family dinner table where everyone else is served a sumptuous meal, but the dreamer is given an empty plate. These dreams can be darker as well, depicting the dreamer imprisoned in the basement, or silenced at gunpoint. They are not necessarily pointing to literal entrapment or violence, but rather to the very real and deep distress we humans feel at being left out or unseen. Themes of loss and grief also feature prominently in relational nightmares (Lemyre et al., 2019).

Studies confirm the connection between dreams and attachment. In both clinical and nonclinical populations, those with insecure attachment styles, especially the fearful type, report more frequent and distressing nightmares than securely attached individuals. Emotional intensity, conflict, and themes of abandonment, betrayal, or being unloved often appear in these dreams, closely echoing the waking preoccupations and attachment wounds of the dreamer (Reed & Rufino, 2019; Sándor et al., 2018).

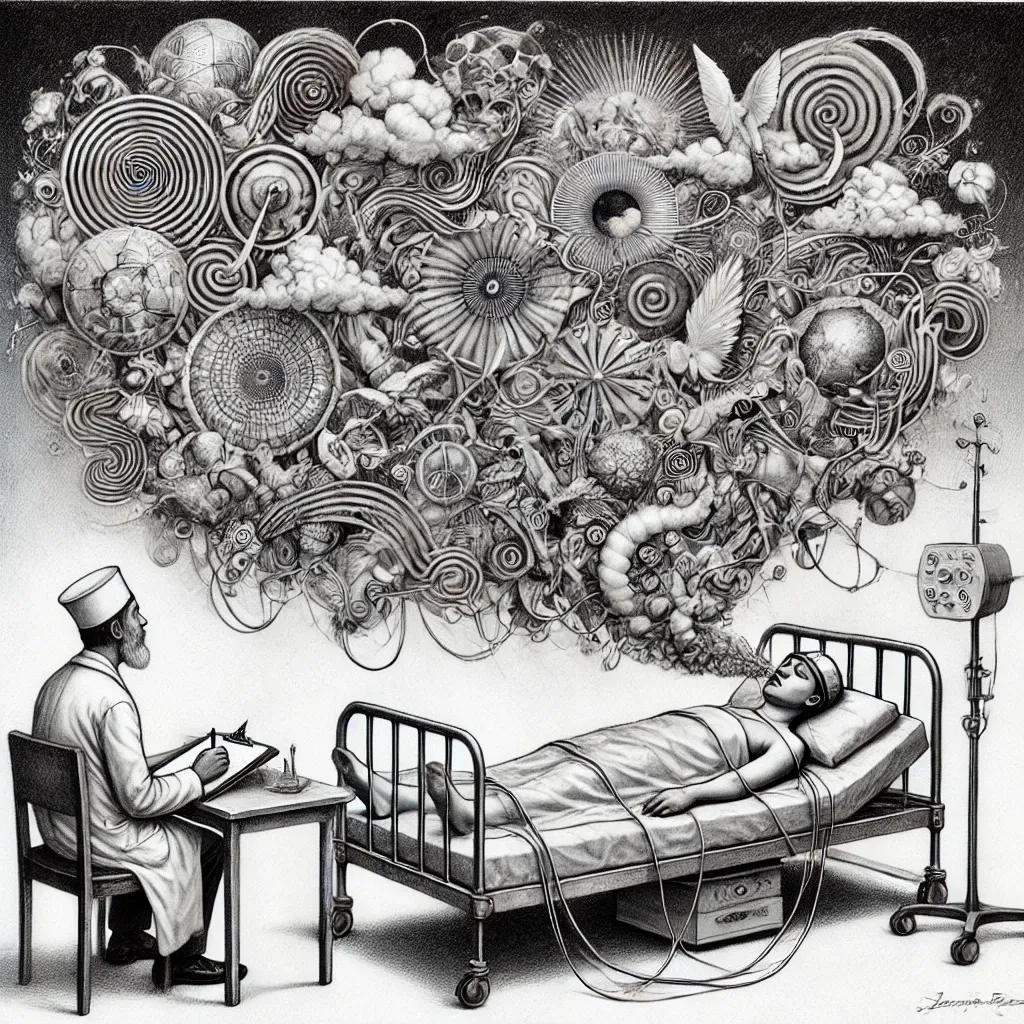

Recent work by Kelly and Kim (2024) takes this one step further by exploring “relational nightmares”—those centered on themes like rejection, humiliation, deceit, and emotional abandonment. Their research supports the continuity hypothesis of dreaming, which proposes that our dream content reflects the same emotional and relational issues that preoccupy us during waking life (Hall & Nordby, 1972; Schredl, 2015). They found that attachment anxiety in particular predicted relational nightmares, and that this effect was moderated by mentalization, which is the capacity to reflect on and understand one’s own and others’ emotional states. Those with high attachment anxiety and low mentalization were especially prone to relational nightmares (Kim & Kelly, 2024).

Dreams also tend to amplify emotional residue that hasn’t found resolution in waking life. As shown in a qualitative study of nightmare sufferers, interpersonal concerns like past relationship breakups, social isolation, and fear of rejection were common triggers for nightmares. These dreams often carried persistent emotional weight throughout the day and influenced how participants perceived themselves and others (Lemyre et al., 2019).

Other research suggests that the emotional tone of dreams—how negative or positive they feel—is also linked to attachment. One study found that anxious attachment was associated with more negatively toned dreams, and this effect was mediated by trait anxiety and depression (Sándor et al., 2018).

Taken together, this growing body of evidence suggests that when we repeatedly dream of someone who hurt us, it’s not because we haven’t let go of the person. Rather, it’s because the emotional imprints of that relationship, particularly those tied to attachment insecurity, remain active. Dreams, especially nightmares, may be the mind’s way of reprocessing those imprints. They can be seen as a cry for the need to tend to persistent attachment wounds. Such dreams are a good target for the effective nightmare treatment practice of imagining the dream forward to a better place.

Clara’s question about why she continues to have nightmares about John can be answered with both compassion and science. Attachment dynamics are deep rivers in our psyche, linked to health, well-being and even survival. And dreams are where the unfinished business of the heart continues to express itself.

Nightmare Relief for Everyone, our self-help course on how to assess and work with your own disturbing dreams is now updated and available here: https://drellis.samcart.com/products/nightmare-relief-for-everyone

References

Belfiore, L. A., & Pietrowsky, R. (2017). Attachment styles and nightmares in adults. Dreaming, 27(1), 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/drm0000045

Hall, C., & Nordby, V. (1972). The individual and his dreams. Signet.

Kelly, W. E., & Kim, H. (2024). Attachment insecurities and relational nightmares: Mentalization matters. Dreaming, 34(4), 372–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/drm0000284

Lemyre, A., St-Onge, M., & Vallières, A. (2019). The perceptions of nightmare sufferers regarding the functions, causes, and consequences of their nightmares, and their coping strategies: A qualitative study. International Journal of Dream Research, 12(2), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.11588/ijodr.2019.2.63708

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2016). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Reed, J. A., & Rufino, K. A. (2019). Impact of fearful attachment style on nightmares and disturbed sleep in psychiatric inpatients. Dreaming, 29(2), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1037/drm0000104

Sándor, P., Horváth, K., Bódizs, R., & Konkolÿ Thege, B. (2018). Attachment and dream emotions: The mediating role of trait anxiety and depression. Current Psychology, 37, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9890-y

Schredl, M. (2015). Continuity between waking and dreaming: A proposal for a mathematical model. Sleep and Hypnosis, 17(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.5350/Sleep.Hypn.2015.17.0101