‘Mary’, a client in my clinical practice, had frequent, bloody, violent dreams and came to love them. She once dreamt of being shot point-blank but did not find this disturbing. The feeling in the dream, and in processing it after, was peaceful, almost spiritual. Another dreamer dreamt of scenes of her family around the table simply eating dinner, yet these dreams struck terror into her heart and left her feeling upset for the entire day.

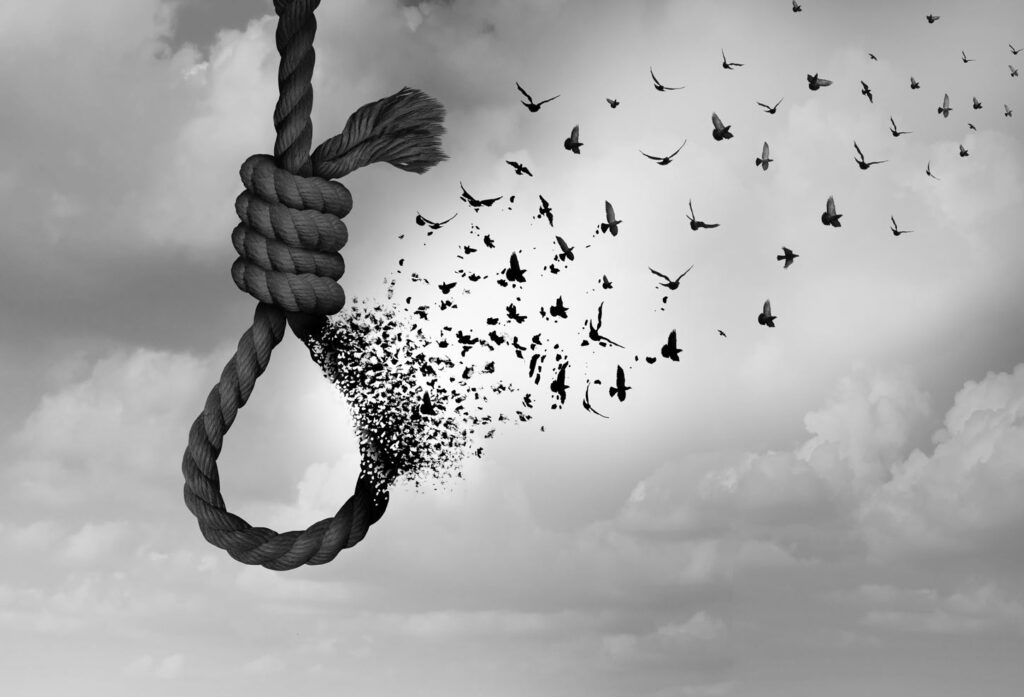

It is often the case that the emotions present in a dream are not congruent with the dream scenario. There are many reasons for this, and many implications for clinicians who ask about and work with dreams and nightmares. The main point is that emotion is a key element in the dream, possibly more important than the imagery itself.

Images in dreams can be highly dramatic, metaphorical and even fantastical. The key is what they evoke. So when asking your clients about their dreams, always inquire about the emotional landscape as well as the visual one. And also understand that dream responses are something we can work with and change.

The words of Victor Frankl (1985) come to mind here: ‘Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response.” We can’t change the fact that our dream forest, however beautiful, is steeped in terror (unless we become lucid, but that’s another topic). However, when we process such a dream with open curiosity, we can change how we feel about it after the fact, and over time, develop a better relationship to our dreams in general.

Mary, for example, had an intense and loving relationship to her dreams, though most of them depicted frightening or violent scenes. And as we worked with them, we discovered that these intense dreams were particularly powerful for engendering deep emotion and change. This is why, as a long-term dream therapist, I look at dream content from a not-knowing stance, never assuming a dream is as bad (or good) as it appears. Instead, I accompany the dreamer on a search for cues of safety and support, and from this place of relative comfort, the whole dream can look and feel very different from the first impression it may have made.

A recent study (Mathes et al., 2022) into nightmare distress confirms much of this clinical experience I describe. The researchers confirmed earlier findings that the level of distress a nightmare brings is significantly influenced by exposure to childhood trauma, and acutely stressful life events. However, violent dream content was less impactful for the 103 participants with frequent nightmares than the emotions they experienced in response to their dreams, a result they did not expect.

The study tracked 103 participants, 59 of whom experienced frequent nightmares, measuring dream recall, nightmare distress, levels of childhood trauma, dream emotions and violent content, and distress related to current life events. The notion that current stressors can bring nightmares, especially for those with a history of adversity, was supported and offers an explanation for the increase in nightmare frequency and distress during the worst of the global COVID pandemic, for example.

However, your response and your attitude towards such dreams can make a real difference to the level of distress they cause. A recent study by Schredl (2021) supports this idea. He found that attitudes toward nightmares and also levels of neuroticism impact how nightmares affect us. But while we can’t change our history of adversity or alter many of life’s stressors, we can change our attitudes and responses toward our dreams. The more we learn and understand about nightmares, and the more we can turn toward our dreams with calm curiosity, the less they are likely to cause distress.

The conclusion Mathes reached about nightmare distress is that “emotional appraisal has a substantial influence on nightmares. This suggests that dreamers can influence dream experiences due to their reappraisal during the dream and probably also in waking life.” My substantial clinical experience working with nightmares suggests that latter is true and may affect the former. In other words, if we befriend our dreams in waking life, we are also more likely to do so within the dreams themselves.

For example, in a few nightmare treatment sessions, I invited ‘Paula’, who experienced frequent recurring nightmares, to gather up any helpful elements she could find in her dreams. She then began to do this from within the dreams. Her nightmares were always harrowing chase scenes, but as she became more curious and comfortable with them, she developed superpowers within the dreams, such as the ability to fly away or disappear. More importantly her feelings around the dreams shifted from abject terror to a sense of adventure. And while the content of these recurring dreams still often begins in similar way, her response, both within and after the dream, has shifted to the point where she would no longer call these dreams nightmares.

References

Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning. Simon and Schuster.

Mathes, J., Schuffelen, J., Gieselmann, A., & Pietrowsky, R. (2022). Nightmare distress is related to traumatic childhood experiences, critical life events and emotional appraisal of a dream rather than to its content. Journal of Sleep Research, e13779.

Schredl, M. (2021). Nightmare distress, beliefs about nightmares, and personality. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 40, 177-188.