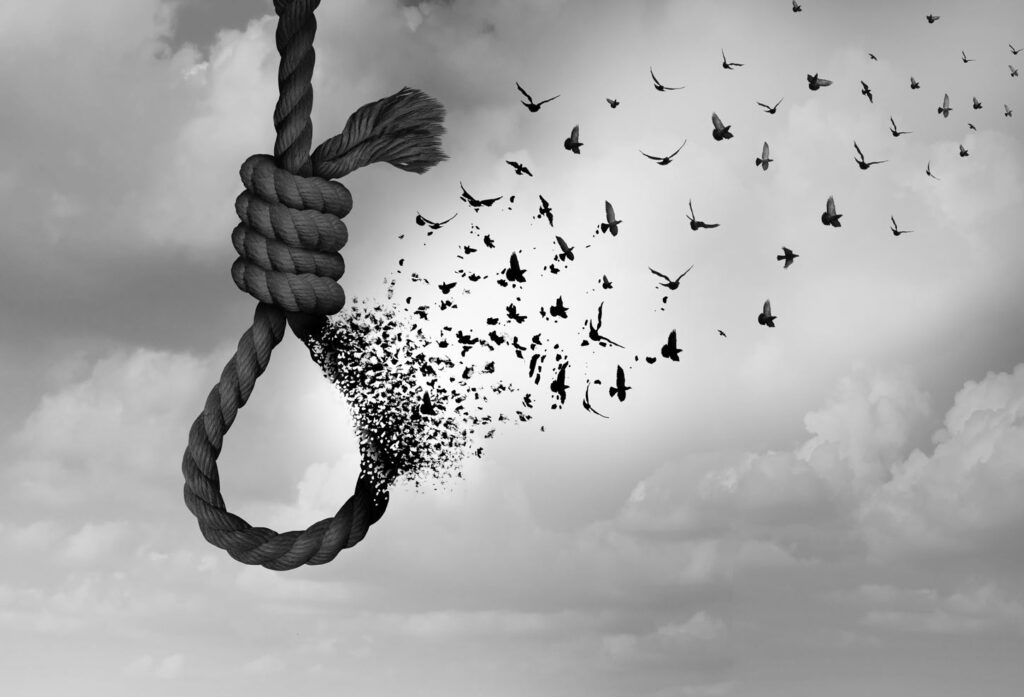

Nightmares quadruple suicide risk in youth, yet overlooked by most clinicians

Scary dreams are common among children, and possibly it is for this reason that they are often overlooked by clinicians. In fact, frequent nightmares can indicate a life-threatening state. It has been well established that nightmares are robustly linked with higher suicide risk in adults, and a recent study has extended this to adolescents.

Children with frequent nightmares are twice as likely to consider suicide and four times more likely to attempt it than kids with fewer nightmares. It’s normal in childhood to have some nightmares, but frequent, chronic, distressing dreams indicate nightmare disorder, which warrants clinical attention, something too few nightmare sufferers receive.

Clinicians drastically underestimate nightmare prevalence

In a recent study, Corner and colleagues (2022) looked at reported rates of nightmare disorder among 806 child psychiatric outpatients, asking both children and their parents about prevalence of nightmares. The researchers found that parents reported 40 percent of these children had nightmares, while 56 percent of the children said they had experienced a nightmare the previous week. Of these children, just 12 (0.01%) had been diagnosed with nightmare disorder, and 16% were given a posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) diagnosis. It appears parents underestimate the prevalence of their childrens’ nightmares by a little, and clinicians underestimate by a lot – if they consider nightmares at all.

The researchers found that very few children in this sample with chronic nightmares had been identified, yet many families expressed desire for treatment for their children. Their conclusion: “We join with researchers of adult populations in calling for routine screening of nightmares.”

A recent systematic review of the prevalence of nightmares in youth found that in clinical populations, 27% to 57% reported nightmares in the previous week and 18% to 22% in the previous month (El Sabbagh et al., under review). By contrast, 1% to 11% of those without a clinical diagnosis reported having a nightmare in the previous week, and 25% to 35% in the past month. Clearly, nightmares are highly prevalent in those children with mental health concerns.

Childrens’ nightmares are highly prevalent, mostly undiagnosed, yet treatable

The hard part of this story is that so many of those with nightmare disorder are undetected and therefore untreated, despite the availability of effective therapies. For example, a recent study looked at treatment of childrens’ nightmares using a sample of 17 children aged 5 to 17. While the researchers were exploring some of the nuances of such treatment, the first important point is that the treatment was effective, with high effect sizes across the board.

The sample was too small to draw firm conclusions about the efficacy of the treatment used – five cognitive-based sessions, including psychoeducation and rewriting the nightmare. However, it does support the considerable evidence that nightmares are treatable.

In this particular study, Pangelinan and colleagues (2022) wanted to know which was reduced first during treatment: nightmare frequency or distress. Because the distress caused by nightmares is considered a driving force in recurrent dreams, the researchers expected distress to drop before frequency, but found the opposite to be the case. Yet both factors were steadily reduced over time, after an initial spike in the distress levels, possibly caused by focusing on the nightmares more than usual.

What makes nightmare treatment effective continues to be a bit of a puzzle and potentially many factors contribute to the success of treatment. I suggest, in my recent article on nightmares and the nervous system (Ellis, 2022), that it is a sense of safety at a physiological level that could underlie nightmare treatment success, and this can be achieved in many ways. Some of these factors are alluded to by Pagelinan: “The steady decline of nightmare frequency and distress over time supports the idea that nightmare treatment is not about an on-off switch of sorts but rather a process by which different skills that address efficacy, hope, relaxation, and sleep skills, in addition to the emotion processing of a nightmare through exposure and rescription, may be important in nightmare treatments.”

The main point here is that while there are many more things to understand about how to treat nightmares, we know enough already to make a real difference. The larger problem we currently face is lack of awareness that nightmares are so prevalent in the clinical population, and that they represent both risk and opportunity.

I am offering a more comprehensive course for clinicians called The Nightmare Treatment Imperative. Learn why treating nightmares is both essential and surprisingly simple.

References

Cromer, L. D., Stimson, J. R., Rischard, M. E., & Buck, T. R. (2022). Nightmare prevalence in an outpatient pediatric psychiatry population: A brief report. Dreaming. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/drm0000225

Ellis, L. A. (2022). Solving the nightmare mystery: The autonomic nervous system as missing link in the aetiology and treatment of nightmares. Dreaming.

Pangelinan, B., Rischard, M. E., & Cromer, L. D. (2022). Examining changes in nightmare distress and frequency across treatment in a child sample: Which improves first? International Journal of Dream Research, 15(2), 198-204.

One Reply to “Nightmares Quadruple Adolescent Suicide Risk”

Working at Walmart

Cheers.

Comments are closed.