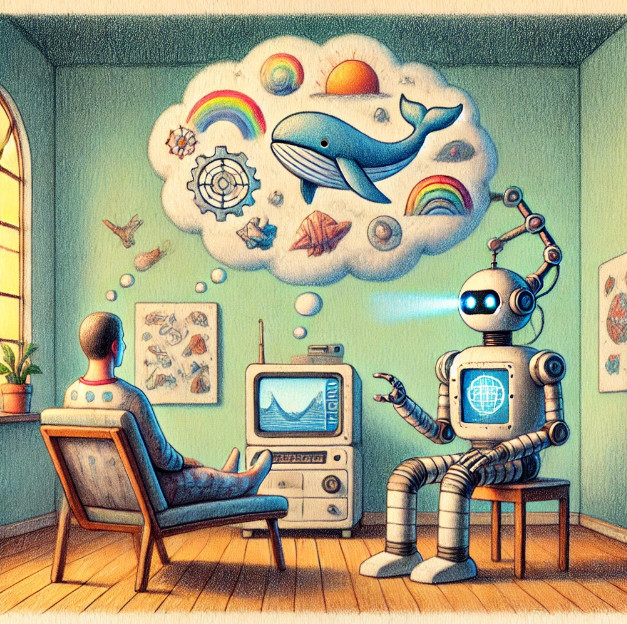

With AI flooding the world with all kinds of applications, of course there are now several AI apps on the market for recording and interpreting dreams – my current favorites are Elsewhere and Temenos. Some of the questions that immediately arise: Does AI do a good job with helping us explore our dreams? What are the pros and cons of using this technology as a way to engage in our dreaming lives?

John Temple, the creator of Temenos, a dream tracking and interpretation app, says the technology is useful, but has limits. He spoke at length on this on the June 20 podcast episode of This Jungian Life (well worth a listen). He said that in the process of testing this program, he sent numerous dreams to be interpreted and found it exhausting. “Your psyche recognizes that it’s not another human soul responding.” He suggests Temenos as a useful tool, but not to overdo it. His sense is that what’s healing in the process of dreamwork is the human connection, something AI can’t replace.

That said, an app can offer interesting suggestions you may not have thought of. If you treat its analysis as coming from one of many members of a dream group, as a reflection to consider and take or leave, it can carry your understanding of the dream forward, sometimes in creatively helpful ways. Temple notes that in dreams, our blind spots are often so evident to others and, by definition, invisible to us. Other voices, including the possible interpretations via an app, enlarge our perspective and may enable us to see the very aspects that we’re missing.

Interpretation aside, dream apps can also be used as a way to record dreams easily and store them all in a single, searchable database – much more efficient than searching through stacks of old dream journals. For example, using the Temenos app, you can speak your dream into your phone and it will transcribe it and store it, and it prompts you to add notes about emotional tone and associations, even generates an image of the dream. Over time, you have a long-term, detailed, searchable record of your dream life, and with this, different questions you can explore – like how a dream element or symbol appears and evolves over time. A premium (ie paid) version of the app lets you join a dream community to share dreams with small groups, or the whole community.

Another great dream AI app is Elsewhere, which offers most of the same functions as Temenos (although its community functions are still under development). I tested it out with a dream I had of an Irish Setter that turns into a fox, a slightly wild and unkempt little creature that is ambivalent about being held by me. The app takes care to offer its interpretation as something to consider, not as gospel, beginning its response with: “If it were my dream, I would interpret is as follows…” It then describes the fox as a “cunning, adaptable, and resourceful” aspect of myself that is perhaps undernourished.

This feels both plausible and a little too reliant on generic meaning. It doesn’t resonate. But a later phrase does seem worth pondering, a suggestion that the dream “could be a reflection of your own desire to balance your wild and free-spirited nature with the need for stability and nurturing.” This feels a little closer to home, and yet again, something is lacking for me. I tend to work with dreams in an embodied experiential way, in this case, to enter into a direct experience of this little fox. What I come away with may be similar in sentiment, but reading the interpretation rather than experiencing my own neglected wild-animal nature is qualitatively so different. Another person holding the space for my direct experience is simply richer and more supportive of what can arise in the field between two people.

What Temple concludes about AI dream analysis is that it is a highly useful tool, but does not replace the human-to-human connection that takes place when we experience our dreams in the presence of another soul. There is something intangible and crucial about the intersubjective field that AI is incapable of generating. It is excellent at recognizing patterns, and is getting more sophisticated so quickly. But human beings are more than pattern recognition machines.

As an aside, I just had a relevant discussion about another kind of AI – active imagination – and intersubjectivity with Serge Prengel that you can listen to here: https://activepause.com/ellis-prengel-active-imagination/

There are now AI-supported apps that can provide therapy – usually the more formulaic forms like cognitive behavioural therapy. Although this cannot take the place of another human, it can offer help that is affordable and accessible. The same is true of dreamwork – although deeply sharing dream experience with another person creates a shared field not possible with a machine, not everyone has access to a dream analyst or dream partner. And the insights and avenues to consider that apps like Elsewhere and Temenos offer can often carry the dreamer further in their own exploration.

Dreams often depict our blind spots and areas to consider that we can be surprisingly obtuse about. Having another viewpoint can widen our perspective, regardless of its source. I find the dream apps useful as records of my dream life. And as interpreters, they are like another voice in a dream group – they offer ways to consider a dream that can lead somewhere or fall flat, and how to respond is entirely up to me.

Join me on substack for an ongoing journey into the world of dreaming!

www.https://dreamsdemystified.substack.com/

Subscribe to get full access to my complete book chapters, publication archives, and to come: recordings, lectures, papers and more.