Porges’ recent article has two main purposes: first, to set out a clear, complete description of the Polyvagal Theory in accessible language to clear up confusion and misconceptions among those who apply and describe it; second, to systematically address criticism of PVT in the literature. This is a summary of the former, especially as it relates to the mental health professions.

Porges never dreamed that when he introduced the Polyvagal Theory (PVT) in 1994, it would attract both intense interest among trauma therapists, and also persistent criticism from some scientists. He wrote The vagal paradox: A polyvagal solution (2023) to correct some of the many misconceptions and misrepresentations about PVT in the literature. He takes pains to express the PVT as clearly as possible, aware that those without education in the foundational sciences required to understand the complexities of this cross-disciplinary theory will continue to apply it and describe it to their colleagues. He notes that “misunderstandings can become misinformation in the digital world.”

The ‘vagal paradox’ paper carefully describes the foundations of the theory, what it covers and does not. It is the clearest, most complete description of PVT to date. The following is a summary of the main ideas Porges presents about PVT, in particular what is new in how he describes the theory and what is of highest relevance to mental health professionals. It does not cover the sections where Porges tackles specific detractors of PVT, most often pointing out why their argument is irrelevant to PVT or shows a lack of understanding of its scope and foundations.

Porges devotes about half of the article to addressing his critics — the main point is that PVT is a respected and testable theory. It has been cited in more than 15,000 peer-reviewed journals. PVT has also been enthusiastically adopted as a non-pathologizing way for therapists to help those with a history of trauma to make sense of their body’s responses to threat, and to recover. As trauma therapists, we can use PVT with confidence that it rests on a solid academic foundation.

The vagal paradox

Much of the description of PVT is unchanged and will be familiar to those who have studied it. The theory came about as a solution to the ‘vagal paradox’ that the vagus nerve in mammals could be both health-promoting and lethal. Porges observed this paradox in his research with preterm infants, for whom the vagus, usually associated with helpful calming, could also stop the heart.

The vagus, a cranial nerve that travels from the brain stem to many organs, is the primary neural pathway of the parasympathetic nervous system. It is primarily sensory, with 80% of its fibres carrying information up from the organs to the brain. The other 20% are inhibitory motor fibres that can act as a brake on the heart and stimulate the gut.

How can the same nerve help or kill? Because it splits into two branches, emerging from the dorsal and ventral areas of the brain stem, and each function very differently. The PVT describes the anatomy, development, evolutionary history, and function of the two (poly) vagal systems.

The PVT had a focus on how the vagus nerve evolved differently in mammals (although modern reptiles and mammals share a common, ancient reptilian ancestry). Porges describes how in mammals, some of the cardioinhibitory neurons migrated from the dorsal to the ventral branch of the vagus to form part of the ‘ventral vagal complex.’ This allowed for down-regulation of threat responses necessary for nursing, co-regulation and attachment, which are distinctly social, mammalian features.

Porges describes how respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) can be used to track the impact of the two vagal pathways through early development. The myelinated cardioinhibitory fibers from the ventral vagal nucleus have a detectable respiratory rhythm. Research has shown RSA has lower amplitude in preterm infants, whose ventral pathways are not yet fully developed, and that this both improves as the infant matures and can be increased further through social engagement. By contrast, when bradycardia (slowed heart rate) is observed in preterm infants, this appears to be mediated mainly by dorsal vagal pathways (though further research is needed to determine if ventral pathways are also recruited).

Dissolution: Evolution in Reverse

An important key to understanding PVT is the Jacksonian principle of dissolution, the observation that evolutionally-newer circuits inhibit older ones except under stress or injury, when changes happen in reverse of this sequence. PVT extends this principle, originally applied to the brain, to include the autonomic nervous system (ANS). Our nervous system develops in this hierarchical fashion: older autonomic circuits (dorsal vagal and sympathetic nervous system) develop first, followed by the newer (ventral vagal, parasympathetic) circuits. It makes sense to Porges that older circuits “would sequentially be disinhibited to optimize survival… under challenge there is a progression that could be characterized as either evolution or development in reverse.”

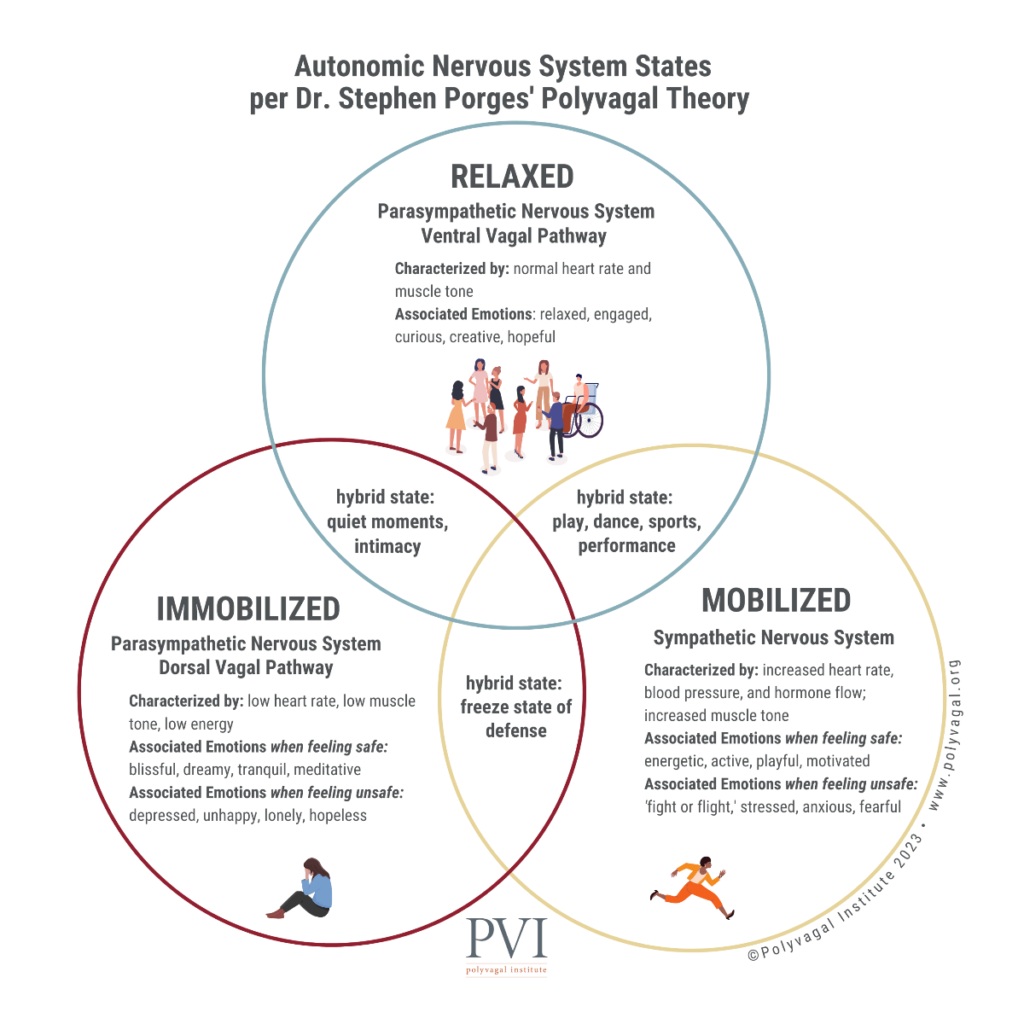

Porges felt it important to note that the dorsal vagus has beneficial functions, especially related to digestive processes. “PVT proposes that when the ventral vagus is optimally managing a resilient autonomic nervous system both the sympathetic and dorsal vagus are synergistically coordinated to support homeostatic functions including health, growth and restoration. However, when ventral vagal influences are diminished… the sympathetic and dorsal pathways are poised to be sequentially recruited for defense.” These steps are more commonly known as fight/flight and then collapse/immobility responses in the popular descriptions of PVT. In the body, these steps are observed as increased heart rate and suppression of the dorsal vagal calming of gut and heart. This sympathetic state is metabolically demanding. To reduce demands, the dorsal vagal influence may surge, lowering blood pressure, reducing heart contractility and clearing the bowel (dorsal vagal collapse).

Ventral Efficiency: A Dynamic Measure

The ventral vagus acts as a brake on the heart, which has an intrinsic rate of 90 beats per minute. “PVT specifically assumes that the vagal brake is mediated primarily through the myelinated ventral vagus and can be quantified by the amplitude of RSA.” Porges introduces a new measure, that of ventral vagal efficiency (VE), to account for the fact that the vagal brake functions in a dynamic manner in response to the environment. This involves evaluation of short sequential shifts or ‘epochs’ to capture the dynamic relationship between RSA and heart rate. Porges lists several studies using VE as a measure, including his own preliminary research showing lower VE for those with a history of maltreatment, which in turn mediated increased symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Porges suggests that VE reflects a disruption in feedback between the heart and brainstem that could lead to body numbness and index autonomic regulation to stressors and psychiatric symptoms. “Blunted VE may be a mechanism through which maltreatment induces mental health risk and interventions aimed at promoting efficient vagal regulation may be promising for improving resilience and wellbeing in trauma survivors.” He suggests VE could be a “powerful, low cost, easily quantifiable and scalable measure” for screening for low ventral vagal efficiency.

PVT: Five Key Principles

In order to understand PVT, Porges suggests there are five key principles. Most of them have already been described in this summary, but they will be explicitly listed below. PVT has evolved since its introduction 30 years ago, in part due to the intense interest and interaction with trauma therapists and survivors who found PVT to be a helpful and liberating explanation for their own embodied experiences. For example, many understood for the first time why they were unable to fight or flee when under attack.

In the process of developing PVT and interacting with the research and clinical communities that have embraced it – the notion of the vagal complex as a process not measurable through standard cause-and-effect principles has emerged. Porges describes PVT as a neural algorithm in which testing by traditional randomized controlled trials does not apply.

Instead, Porges envisions an index of autonomic signatures describing autonomic responses to specific situations. “Perhaps the most informative aspect of such an algorithm would be to identify the autonomic pathways that would support the ability to down regulate threat to enable mobilization and immobilization to occur with trusted others and not trigger defense… It is this process of functionally liberating mobilization and immobilization from defensive threat driven strategies that PVT hypothesizes to have supported the emergence of social behavior and cooperation in species of social mammals.”

This leads naturally to the first principle:

- Autonomic state functions as an intervening variable

This principle stresses the capacity of the ANS to dynamically respond, adapt, process and recover from challenges. “PVT emphasizes an important perspective missed by correlational research – how the ANS is part of an integrated response, not a covariate.” This notion transforms how research would be conducted since it emphasizes integration of autonomic, cortical and somatic systems, shifting research targets from correlation to all of the parameters that mediate such integration. Porges said this could curb the tendency to generate faulty causal inferences from high correlations that can lead to inappropriate treatments and poor outcomes.

- Three neural circuits form a phylogenetically ordered response hierarchy that regulate autonomic state adaptation to safe, dangerous and life-threatening environments.

This is the cornerstone of the PVT, and well documented in this and other polyvagal literature, however Porges continues to refine his description. The PVT emphasizes there are three neural circuits that regulate and shift autonomic state in response to signals of safety, danger and life threat. PVT describes the mammalian response hierarchy in terms of biobehavioural scripts initiated.

“The phylogenetic sequence is initiated by a dorsal vagus, followed by a spinal sympathetic system, and finally with the ventral vagus. By identifying the biobehavioural scripts of each of these circuits, we become appreciative of the efficiency of the three neural circuits in an attempt to optimize survival,” Porges wrote. These scripts help us to identify when the system in a safe or threatened state, and if the latter is fight/flight or immobilization. PVT shows how in a safe (ventrally-mediated) state, the system supports health, growth, restoration and sociality.

- In response to challenge, the ANS shifts to states regulated by circuits that evolved earlier consistent with the Jacksonian principle of dissolution, a guiding principle in neurology.

This has been described above.

- Ventral migration of cardioinhibitory neurons leads to an integrated brainstem circuit (ventral vagal complex) that enable the coordination of suck-swallow-breathe-vocalize, a circuit that forms the neurophysiological substrate for an integrated social engagement system.

The ventral migration of cardioinhibitory neurons became integrated in the regulation of the striated facial muscles used in ingestion and expression. This led to the formation of a social engagement system in mammals that enables a shift from states of defense to those of connection through co-regulation. The PVT describes how the presence of trusted others, especially if they project calm and safety through voice and gesture, can help a person shift into a calmer state. Such features can also be incorporated into trauma therapy.

- Neuroception: reflexive detection of risk triggers adaptive autonomic state to optimize survival.

Porges coined the term ‘neuroception’ to emphasize that the scripts initiated by the ANS in response to perceived safety and threat operate outside of awareness and are not under cognitive control. Because these are survival responses, the time it takes to assess and think about a response might be too long, hence these processes are reflexive, “unimpeded by intentionality and cognitive appraisal.”

In conclusion…

This article has not only offered a complete, and accessible summary of the development and current state of the PVT, but has also shown that it rests on a firm academic foundation. In addition, it paves the way for future research, and prescribes a significant shift in how such research ought to be conducted to faithfully capture the dynamic and integrative nature of the ANS. Most importantly for clinicians, PVT offers a humane and hopeful path for those who have suffered severe trauma – both a way of understanding symptoms, and a supportive path toward healing.

Reference:

Porges, S. W. (2023). The vagal paradox: a polyvagal solution. Comprehensive Psychoneuroendocrinology, 100200.