Dreams as a picture of the nervous system, and an avenue for state shifts

It’s beginning to dawn on me that not just nightmares, but all dreams can be seen as an expression of the nervous system. They are images direct from the body, far less filtered by our internal censor than waking thoughts — they are more image-based, more visceral and fluid. Spending time with our dream images in a calm and curious way can be inherently regulating, and I am beginning to suspect why this is so.

The late Ernest Hartmann, a celebrated dreamworker and researcher, said two things that I want to follow up on in this context. The first is, “The nightmare is the most useful dream.” This is not meant to dismiss the real distress and terror that our worst dreams can bring. It’s that nightmares represent an extreme state, and as such, one that we can learn the most from.

Linking nightmares and the nervous system

I’ve spent the last couple of years investigating the link between nightmares and the autonomic nervous system (ANS) through the lens of polyvagal theory. Although I think the implications of this for nightmare formation and treatment are still largely unexplored, I started this ball rolling with the recent publication of an article with the optimistic title, Solving the Nightmare Mystery in which I imply that the role of the nervous system is a missing link in our understanding of how to treat nightmares (Ellis, 2022).

I have been sitting with those who experience deeply disturbing dreams for many years now, one of the main things I do to help is facilitate the search for, and embodiment of, cues of safety that help alter their perception and experience of these dreams. They tell me this embodied process of dreaming their dreams forward (called ‘rescripting’ in modern nightmare treatment literature), changes how they hold the dream in their body. Typically, the memory remains, but the charge dissipates, after a successful session.

Nightmares are dramatic, and there is clear autonomic activation during sleep state shifts for those who experience them frequently. Nightmares are easily recalled and their impact is tangibly felt, as is the relief one experiences when they begin to fade or shift into a more benign form. This is useful because when a phenomenon is loud and colorful, we can more easily see it.

Dream images as nervous system state and shifts

However, in a recent class I teach on the clinical use of dreams, a dreamer brought an image of a dark, still woman in a tub that had sat so long the water had gone cold. Her impulse, in dreaming this forward, was to turn on the hot water faucet, to bring some warmth to the bath and to the woman’s body. Entering the dream further, she noticed the tub itself, and it was older, more ornate and beautiful than the one is her current bathroom, where the dream was set. Her own demeanor changed in this process or warming the bath, her face coloring and smiling as she described making the bath a sanctuary, adding scent and oil and dipping into the enjoyment of it. Later, she told me the shifts continued in the coming days: “I continued to experience “mini shifts” in the following days and was able to access and carry the felt sense of the warmth and beauty of the bath into many areas of my daily life. I noticed I feel more present when I bring a sense of aesthetics, in the form of a little beautifying and warming detail, when I have to tackle some of the mundane daily tasks and responsibilities, which were weighing me down lately.”

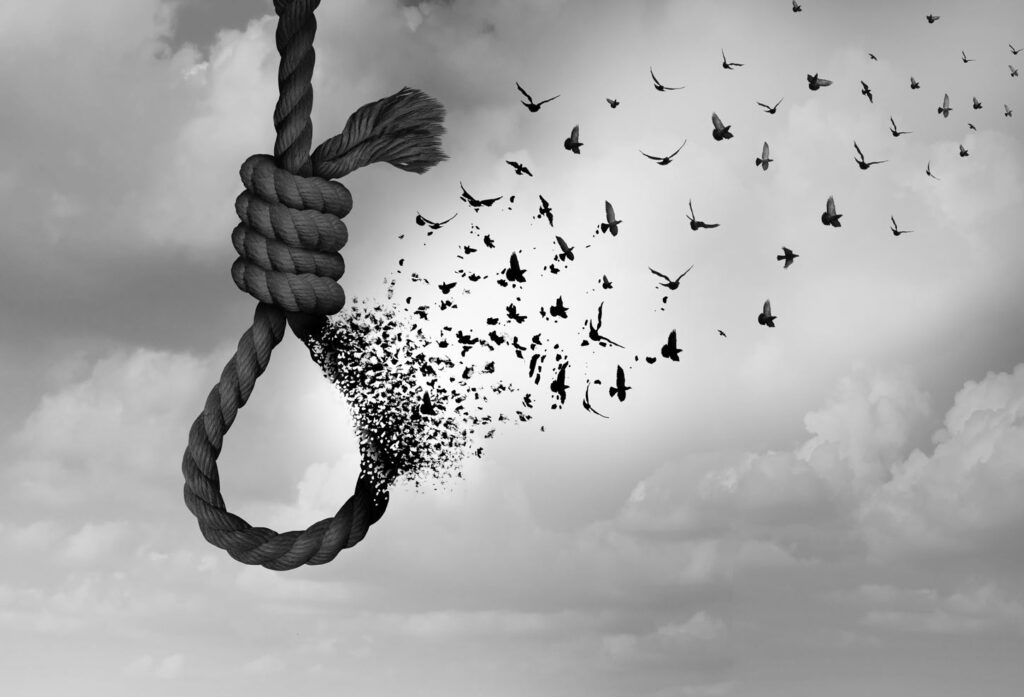

This entire dream process could be seen as an image of the nervous system as it shifted from a cold, immobilized (dorsal vagal) state, into one of connection and animation that was clearly visible on her face. Her fellow classmates remarked on the change, as her physiology demonstrated a clear shift into a state of social engagement and warmth (ventral vagal). This kind of shift is typical in working with dreams. The images from nightmares are clear representations of autonomic states. Activation or fight/flight – being chased or engaged in a battle – are some of the most prevalent nightmare themes. The leap I have made is simply that nightmares are the most obvious expression of what happens in all dreams. They are our bodies expressing in image and sensation our fluctuating internal state. They are doorway into its expression, particularly valuable for those who have trouble hearing what’s going inside.

Dreamwork as a way to metabolize and regulate emotion

This brings me to another of Hartmann’s famous statements: that dreams are a ‘picture-metaphors’ for our most salient emotional concerns. Sometimes our most pressing feelings are repressed, historic or fleeting enough that we don’t think about them during the day. But our dreams have an uncanny way of picturing what matters most, even if we have repressed it. Our bodies carry the charge of feelings and memories that are unmetabolized, and these find expression in our dreams.

My sense, which is shared with many dreamworkers and researchers, is that a purpose of dreaming about emotion is not to upset us but to help us process and shift such feelings. Sometimes, the dreams do this all on their own, like a nocturnal therapist, and sometimes it really helps to have another person process the dreams with us. One idea that attention to the nervous system and polyvagal theory has taught us is that we humans (and all mammals) function better together than alone. Sharing our dreams and bringing them into company and the light of day helps them do their job better. And more and more, I’m beginning to think that a large part of their job is expressing and regulating the state of our nervous system.

References

Ellis, L. A. (2022). Solving the nightmare mystery: The autonomic nervous system as missing link in the aetiology and treatment of nightmares. Dreaming.

Hartmann, E. (1999). The nightmare is the most useful dream. Sleep and Hypnosis, 1(4), 199-203.

Hartmann, E. (2010). The dream always makes new connections: the dream is a creation, not a replay. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 5(2), 241-248.