Social connection has always been the beating heart of a healthy, fulfilling life. For millennia, philosophers, poets, and scientists have agreed: we thrive in relationship, and we suffer in isolation. Our dreams may have been whispering this truth to us all along.

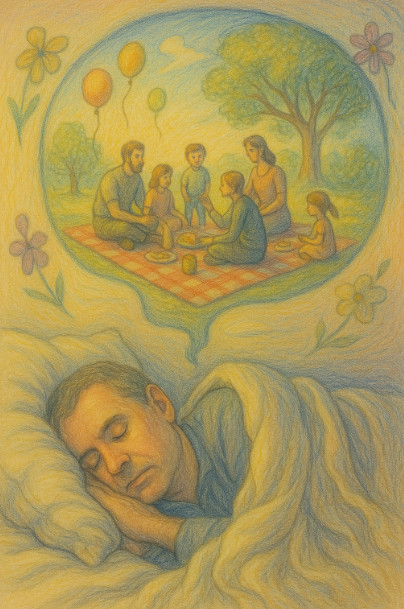

New research is uncovering the fact that our dreams are profoundly social. Every night, as we slip into sleep, our minds stage encounters, conversations, reunions, and conflicts with people from our lives—sometimes weaving in strangers too. Far from being random nonsense, these nightly stories appear to serve a deeper purpose: keeping us connected, even in the absence of physical presence.

A recent study led by John Balch and colleagues brings this idea vividly to life. Over two weeks, participants recorded their dreams, while researchers tracked their daily interactions and core social networks. The researchers found that dreams were populated with a mix of familiar faces and unknown figures, a nightly gathering of friends, family, and mysterious strangers. But it wasn’t just a reflection of who they’d seen that day. Certain patterns suggested something more deliberate, almost purposeful, was happening in the dreaming mind.

The Social Cast of Our Dreams

Balch’s team discovered that the likelihood of someone appearing in a dream was tied to how much interaction they had with the dreamer during the day—but with an interesting twist. While daily contact generally increased the chance of dreaming about someone, this pattern reversed when it came to close family members like parents and siblings. If participants hadn’t seen their closest loved ones during the day, they were actually more likely to dream about them that night.

In other words, our dreams may compensate for absence, conjuring beloved figures to maintain emotional bonds across distance or time. If you haven’t called your mom in a week, your dreams might bridge that gap for you. Our subconscious, it seems, refuses to let important connections fade quietly.

This insight resonates on an intuitive level. How many times have you dreamt of someone you miss? Or found yourself puzzling over why a long-lost friend appeared in a dream out of nowhere? Perhaps it wasn’t random at all. Perhaps your dreaming mind was tending to your relationship while you slept.

Social Simulation or Mere Reflection?

These findings add fuel to a lively debate in dream research: are dreams functional rehearsals, or just reflections of waking life? The Continuity Hypothesis suggests dreams mirror our daily concerns and activities. Spend the day stressed about work, and your boss might show up in your dreams. Nothing creative, just emotional spillover from the day.

The Social Simulation Theory (SST) proposes something richer: that dreams actively simulate social interactions to help us maintain, rehearse, and strengthen our relationships. Think of dreams as a low-stakes playground for working out conflicts, nurturing bonds, and exploring emotional territory.

Balch’s research lends support to SST. The fact that we dream more of absent loved ones suggests dreams step in to maintain connection when waking opportunities fall short. Similarly, research has found that even when people experience prolonged social isolation, their dreams remain stubbornly social—populated with family, friends, and familiar figures. It’s as if the brain refuses to accept social deprivation, filling the void with imagined encounters.

This social resilience in dreams aligns with a deeper biological truth: connection isn’t optional for humans, it’s essential.

Dreams, Loneliness, and the Deep Need for Belonging

Modern neuroscience and psychology have caught up to what dreams seem to have been signaling all along. We are wired for connection, and lacking it takes a toll—not just emotionally, but physically. Research shows that chronic loneliness raises the risk of heart disease, stroke, depression, anxiety, and even premature death. Some studies equate the health risk of persistent social isolation with smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

In fact, in 2023, the U.S. Surgeon General issued a stark warning: we are living in an epidemic of loneliness. And it’s killing us—slowly, silently, but profoundly.

Against this backdrop, the social richness of dreams becomes more than an academic curiosity. It is almost like an act of inner resistance. Even when our waking lives fracture our social ties—whether through busyness, conflict, physical distance, or societal disconnection—our dreaming mind keeps the connection alive.

It’s not hard to see why evolution would favor this. Strong social bonds have always been a key to survival. The support of family, friends, and community buffers us against life’s hardships. Conversely, social rupture and isolation leave us vulnerable. Perhaps dreams help us keep our emotional alliances intact, rehearsing forgiveness, reunion, or even imaginary closure. It’s emotional maintenance work we don’t consciously schedule—but our dreams do it anyway.

A Nightly Message Worth Heeding

If dreams indeed help us stay socially tethered, they’re sending us a powerful message—one that extends beyond sleep: tend to your connections. Pay attention to the people who appear, over and over, in your dreams. Reach out to the loved one you haven’t spoken to in months. Nurture friendships you’ve let drift. Your dreaming mind is already doing this work at night; perhaps your waking mind needs to follow its lead.

In this way, our dreams are not just reflections of our relationships, but gentle reminders of what—and who—matters most.

So the next time you wake up from a vivid dream about an old friend, or your childhood home, or a family dinner, pause before you brush it off as random. Consider that your mind may be trying to keep those emotional threads alive, weaving them into the fabric of your inner life so they don’t unravel.

We are, after all, deeply social creatures—even in our sleep.